Story by Bernard Little

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center’s electrophysiology laboratory recently performed the Department of Defense’s first pulsed field ablation (PFA) to treat atrial fibrillation (AFib).

PFA offers a safer option for AFib, according to retired U.S. Navy Capt. (Dr.) Matthew Needleman, a clinical cardiac electrophysiologist. Needleman led the team that performed the procedure on an active-duty service member with a deployment-limiting arrythmia, enabling the service member to be globally deployable.

“AFib is a chaotic rhythm in the heart’s left atrium (chamber), which quivers and doesn’t contract normally causing a host of problems,” Needleman said. He explained that symptoms can include palpitations, chest pain, dizziness or fainting, fatigue or weaknesses and shortness of breath. “Some people describe feeling like a fish is flopping in their chest,” he shared.

Needleman noted that some of the more severe challenges of AFib can include an increased risk for stroke, heart failure, and dementia.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 12.1 million people in the U.S. will have AFib by 2030. Globally, around 50 million people, or 10 to 15 percent of adults will have AFib by then. “It’s a common problem that increases with age,” Needleman said. He added that other risk factors for AFib including high blood pressure, obesity, and sleep apnea, are increasing in the general population. Other risk factors include lack of physical activity, excessive alcohol consumption, and nicotine use.

In addition to PFA, treatments for AFib include medications and other standard procedures such as cardioversion (electrical shock to restore the heart’s natural rhythm), catheter ablation (radiofrequency waves or freezing to the target source of the irregular heartbeat) and left atrial appendage occlusion (closing a small pouch on the left atrium to reduce the risk of stroke).

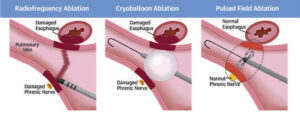

Needleman explained that standard ablation procedures can carry a risk of complications including bleeding, perforation, and damage to the esophagus, phrenic nerve, blood vessels, and heart valves.

“Initially [about the early 2000s], we only had radiofrequency ablation, which is a kind of heating ablation,” he said. He added about 15 years ago, cryoablation, or a freezing energy, began being used as a treatment for AFib. “One heats and one cools to kill the [abnormal] tissue. The problem with both of them is that thermal ablation causes collateral damage [to the esophagus, phrenic nerve and narrowing of the veins],” he explained.

With PFA, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in January 2024, Needleman explained that high energy is used for a very short duration, “less than a second, which causes irreversible electroporation” to make cells causing AFib inactive rather than destroying them.

“It doesn’t cause phrenic nerve damage,” Needleman added. The phrenic nerve controls the diaphragm and is essential to breathing.

To perform the PFA, Needleman threads a thin tube (catheter) from the patient’s groin to the heart’s upper chamber. The catheter forms a rounded basket shape and is positioned in the pulmonary vein. Short bursts of electromagnetic waves are applied to the heart tissue causing AFib, creating microscopic holes in the cells. This process, called electroporation, prevents electrical impulses from causing AFib. The catheter is then flattened and removed.

Patients usually go home the same day following the procedure, and over the next few months, stop taking medications for AFib.

“The [PFA] procedure seems to go a little bit quicker [than other AFib procedures], the recovery time seems quicker, and patients so far are doing really well,” Needleman added. “All of them have gone home the same day [following PFA], and around three months, we can clear them to go back to normal duty,” he shared. He said the procedure takes approximately two hours.

Since Needleman and his team performed the initial PFA on June 17, they have done the procedure on at least five other active-duty patients. The team that performed the first procedure included interventional cardiologist U.S. Navy Capt. (Dr.) Robert Gallagher, U.S. Army Maj. (Dr.) Ardalon Farhat Sabet, Mark Haigney, nurse U.S. Navy Lt. Eric Taylor, Petty Officer 3rd Class Spencer Hardtner, Seaman Tahsia Aziz, Hospitalman 2nd Class Logan Rees, Bevin Cawood, anesthesiologist Christian Popa, Bryan Robinson, health system specialist Marie Ann Macomb Ylanan, and Khalil Abdul Azim.

“AFib can be one of those things for our active-duty population that can be deployment and career limiting,” Needleman said. “If we do this procedure, we can get rid of the AFib or significantly reduce the symptoms, and many of those patients are able to return to full military service. This is really important for some of our special warfighters and pilots.” He added the goal is to minimize and even stop long-term medication use of patients by reducing and stopping AFib symptoms.

He added PFA is also being offered to retirees and other Military Health System beneficiaries.

“I’m proud to work in an organization that really doesn’t just say they care so much about quality and safety, they actually make the investments to do the right things for patients,” Needleman shared. “I’m proud of the organization for allowing us to be the first in DOD to offer this innovative, game-changing technology for our patients.”

This is not the first time Needleman has been involved in performing cutting-edge technology at Walter Reed. In 2017, Needleman was part of a team working on a new leadless pacemaker. This device contacts heart tissue directly without leads, reducing the risk of complications like lead fractures, dislodgement, or infections which can lead to their death.

Needleman shared that leadless pacemakers are implanted directly into the right ventricle in the heart, solving a significant portion of pacemaker lead problems.