Story by Sgt. 1st Class Neil W. McCabe

Army Reserve Medical Command

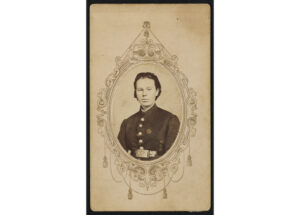

[CAMP PARKS, Calif.] The site director of the Medical Readiness and Training Command’s Regional Medical Site-Medical here reflected upon her 2019 history master’s thesis “Women Who Wear the Breeches: The Representation of Female Civil War Soldiers in Mid-Nineteenth Century Newspapers” for Women’s History Month.

“I lived and breathed nothing but these women for probably 18 months while I was writing and researching the thesis,” said Lt. Col. Danni Leone, who earned her master’s degree from the State University of New York at Brockport.

The colonel said she always appreciates Women’s History Month for the opportunity it presents for stories that otherwise would not get the attention they deserve.

“It’s important to see people like you represented, and for so many years in our culture, so many different people were not represented,” she said.

“Hopefully, in the future, it’ll just be history, and it’ll include all of us,” she said.

“Women, people of color, people of different, all different backgrounds that we all participated in history and that we all contributed to history and the world and our country, and so that we don’t have to differentiate women’s history,” she said.

Leone: Thousands of women served in the Civil War disguised as men

“My basic argument is that the estimated number of female soldiers who fought disguised as men in the Civil War is much higher than previous historians have reported,” Leone said.

The colonel said that the number that has become the accepted tally is 400, which is derived from Mary A. Livermore’s 1890 memoirs, “My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative or Four Years Personal Experience as Nurse in the Union Army, and in Relief Work at Home, In Hospitals, camps, and at the Front During the War of the Rebellion With Anecdotes, Pathetic Incidents, and Thrilling Reminiscences.”

The problem was that although Livermore used the 400 number, the Civil War nurse also wrote that she was convinced there were far more women disguised as men because so many were disguised.

“My basic argument was that I think there were probably thousands,” she said. “Most of them that did it probably weren’t found out, but the number 400 is usually ascribed to the ones that were found.”

To overcome the barrier of the disguise, the colonel said she relied principally on newspaper accounts of women discovered during their attempts to enlist, or their deaths or the need for medical care, she said.

“The thesis also highlights what a vastly different it was for women in America and why it was much easier than it would be today to disguise one’s gender within the ranks of the Army,” she said.

The native of Jamestown, New York, said there were strict gender rules for how people dressed during the Civil War.

“In short, women wore dresses, and men wore pants,” she said.

“In fact, many states had laws prohibiting the wearing of garments of the opposite sex, and women were arrested for wearing pants or breeches,” she said. Most people had never seen a woman in pants. The eyes do not see what the brain does not expect to see. A woman in pants, let alone a woman in a military uniform, was something most people could not conceive.”

Leone, a civilian nurse who joined the Army at 40, said that while many women were caught trying to enlist, it was not always a formal process, so many slipped through.

“There were no real identification documents like we have today,” she said. “A person could give any name for themselves, and as I note in the thesis, the entrance physical often consisted of little more than a handshake.”

The colonel said that when she began her research, she hoped to establish evidence that these women serving as men were feminists, but instead, she found that their motivations were much simpler.

“These women were, by and large, not fighting for women’s equality,” she said.

She said most women followed their loved ones, such as husbands and boyfriends. “I would say it might have been more than half, but at least half, if you include daughters, following fathers, sisters, following brothers.”

The other reasons the colonel found were patriotism on both the Union and Confederate sides, the chance to make their own living and adventure.

Others were women living as men before the war, so she said that they followed the expectations for other men when they enlisted. “They were naturally expected to enlist.”

Leone said some Black women served in the Union Army, but there were no Black regiments in the Confederate Army.

While newspaper accounts of white women serving as men during and after the war celebrated their exploits and were nearly always positive, there were few accounts of Black women, she said.

“Black women were widely considered to be suited to fieldwork and hard labor,” she said.

“The newsworthiness of white women who masqueraded as men was because they were straying so far from normal gender expectations, but racialized beliefs about black women did not hold them to the same gender expectations,” she said.

“For this reason, I believe that the number of black women who fought in the Civil War is grossly underrepresented in the newspaper coverage of the time,” the colonel said.

In her paper, the colonel described how one Black woman serving in the 29th Connecticut Infantry (Colored) was discovered after she gave birth, and one of her sergeants was quoted asking: “Did you ever hear of a man having a child?”

Another black woman in the paper, Maria Lewis, served for 18 months in the 8th New York Cavalry, posing as a white man.

Frances E. Hook

Leone said Frances E. Hook followed her brother, her only living relative, into the Army, serving as Frank Henderson. Her brother enlisted in the 11th Illinois Infantry so she would not be left alone at home.

“It was reported that, like so many female Soldiers, she won the universal esteem of her officers,” she said.

“In April 1864, The New York Times reported that she was captured by the Confederates and tried to escape,” she said.

When she attempted to cross the Tennessee River with several prisoners, she was fired at and struck in the calf of the leg, she said.

“Though no more than a flesh wound, it was painful, and in this condition, she was obliged to march several miles handcuffed and even shackled,” the colonel said. “In addition to the daily horrors of war, female prisoners like Frank Henderson also endured torture and the even more unsanitary conditions of the stockade.”

Florina Budwin

“One of the powerful ones I just couldn’t shake was the story of Florina Budwin,” the colonel said.

Budwin followed her husband into a Pennsylvania artillery unit, Leone said.

“They were both captured and taken to the Confederate stockade in Florence, South Carolina, and she continued her deception even after her husband was killed by a prison guard,” she said.

“Unfortunately, she became ill with pneumonia and died in prison one month before all of the sick prisoners at the Florence stockade were paroled,” she said. “She is buried in the Florence National Cemetery.”

Pauline Cushman

Pauline Cushman was an acclaimed actress before the war, Leone said, and her story was reprinted in newspapers across the country and probably embellished.

“She was suspected of being a rebel, and she was arrested by federal authorities,” she said. “To prove her loyalty, she agreed to be a spy for the Union.”

Cushman, who often wore a military uniform, was discovered when documents proving she was a spy were discovered in her gaiters by a Confederate woman, she said.

The actress-spy was tried and condemned to be executed, Leone said.

“The execution was postponed due to her coming down ill, and she was saved when the Union Army captured the town where she was being held,” she said.

Leone: These stories were lost, then rediscovered

The colonel said the stories about women serving as men in the Civil War were plentiful and positive, but going into the 20th Century, the stories stopped being repeated, and when they were repeated, they were no longer positive.

“Scholars revised the history of the female Civil War Soldiers, painting them as mentally ill, masculine women unworthy of remembrance,” she said.

“The stories faded out of the public consciousness as each generation learned less and less about them,” she said.

She said this may be because, at the turn of the last century, women were demanding changes in their social, economic, and political status—and it was more difficult to deny these changes if it was acknowledged that women had served in uniform for their country.

“As time passed and women began to pose a real risk to the patriarchal order with their calls for equality, the men in power constructed a history that supported a patriarchal national narrative and dispensed with any facts that contradicted it,” she said.

Leone said that after the 1960s, scholarship into women serving in the Civil War disguised as men became socially acceptable as society’s view of women and their roles and rights evolved to where it is now.

“Still, it was nearly a half-century after the Civil War before women finally earned the right to vote and nearly a century and a half after the last woman fought on a Civil War battlefield that the Army finally lifted the ban on women in combat in 2013.”